I have just finished reading Chapter 7 of Martin Weller’s The Digital Scholar, entitled “Public Engagement as Collateral Damage”. In this chapter, Weller argues that there is a distinction between “big OER” and “little OER” projects, and makes a case for universities engaging in more little OER projects.

“Big OER” projects often mean broadcasting or publishing well-researched, high-quality educational material with high production values, a clear purpose and a target audience. The advantage of this approach is that the output is high quality, and recognisable as the university’s “brand”. However, projects such as these come with a high price tag and central planning and coordination.

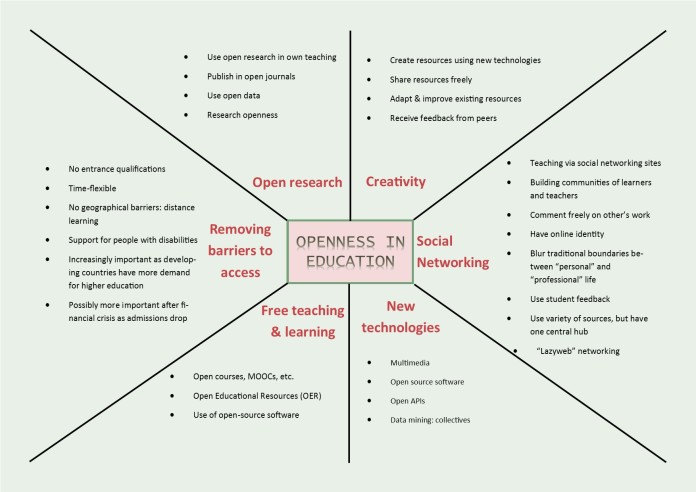

“Little OER” projects refer to “the long tail” of public engagement – i.e. material with relatively small numbers of views, which total a large number of views when taken as a whole. Weller argues that with a relatively small adaption to existing closed practices, universities can, as a whole, make a large difference to open education. This can include making lecture notes and reports on meetings made open. The advantage of this approach is that it doesn’t require central planning, or a clear purpose, or expensive high production values.

One issue that occurred to me in considering big versus little OER was the impact on the time that university staff have available. Although opening up existing practices should not require a huge amount of time – that would defeat the purpose of “little OER” – it does create a pressure on potentially time-poor staff. In my experience, innovations such as these often create an extra burden on staff without anything else being taken away. For example, publishing the outcome of meetings openly should take the place of writing a (closed) report – not supplement it.

In addition, encouraging staff to open up their teaching practices might be a difficult sell. Again, in my own practice, I have noticed that a lot of teachers do not like to be observed, as it makes them feel they are being judged. Who is going to convince them that their every professional choice is not going to be scrutinised under the watchful eye of the general public? And if staff development is necessary to bring about this change in culture, does that not require time and money, which is what little OER is meant to minimise the demands on?

Lastly, there is a question of rights. If a practitioner chooses to make his/her teaching material openly available, who owns the copyright/creative commons license? The practitioner or the institution? (This is not a rhetorical question – does anyone know the answer?)

I’d love to hear if anyone has any answers or challenges to what I’ve said! Leave a comment below!